Days before Attorney General Merrick Garland appointed special counsel Jack Smith to investigate former President Donald Trump, experts who had been following the Justice Department investigations questioned its necessity. Mr. Smith was appointed on Nov. 18, 2022.

Would the appointment of an “independent” lead prosecutor undermine the Justice Department’s own appearance of independence from politics? Would the newly appointed prosecutor slow down the case?

Those concerns have now materialized, though not for the predicted reasons.

What Are Special Counsels For?

Attorneys general have been hiring special counsels since before the Justice Department was established in 1870, via a statute that specifically set guardrails on the hiring and payment of outside attorneys as special counsel.A century later, with the Watergate scandal, Congress decided that there was a need for a truly independent prosecutor to investigate senior executive branch personnel, including the president. In 1978, Congress passed an ethics bill that created the Office of Independent Counsel.

While controversial, the law was reformed and reauthorized more than once before Congress let it expire in 1999.

Just before it expired, the Justice Department under Attorney General Janet Reno created its own set of regulations for appointing a special counsel.

The department determined that attorneys general may appoint a special counsel if a case “would present a conflict of interest for the Department or other extraordinary circumstances,” instructing the attorney general to then select someone from “outside the United States Government.”

These past few years, the Justice Department has found plenty of “extraordinary circumstances.”

In 2022, Mr. Smith was appointed to investigate matters related to President Trump.

Experts Weigh In

When President Trump appealed his presidential immunity defense to the U.S. Supreme Court, former U.S. Attorney General Edwin Meese III was quick to submit an amicus brief arguing that before the case could proceed, the high court should settle the matter of whether a private citizen can lawfully be given the authority to impanel a grand jury, investigate, and prosecute a former president.The amici argue that Mr. Smith wields the power of a “principal or superior officer” without being appointed through the lawful process as required under the Appointments Clause.

The correct avenue would have been to appoint a currently serving U.S. attorney as special counsel, or to appoint an outside special counsel that serves under a U.S. attorney, Mr. Meese, Mr. Calabresi, and Mr. Lawson argue.

Mr. Meese, Mr. Calabresi, and Mr. Lawson filed another amicus brief in support of the motion in this case, as did other experts.

In a 1867 case, United States v. Hartwell, the Supreme Court defined the difference between a contract employee and officer. Justice Noah Swayne wrote that an office “embraces the ideas of tenure, duration, emolument, and duties.”

A decade later, the high court relied on these four factors in United States v. Germaine, updating the definition to find that officers must be in positions that are “continuing and permanent, not occasional or temporary.” The Germain decision was cited in subsequent cases that dealt with differentiating “officers” from “employees” of the United States.

“The nature of the special counsel’s position is that it disappears once this prosecution is over,” Mr. Tillman told The Epoch Times. “It’s not a permanent position; it is not a continuous position.”

And if Mr. Smith is not an officer, “his prosecuting anyone is entirely unlawful,” Mr. Tillman said. Also diverging from the previous group of amici, he posits that the case could be salvaged if handed over to a U.S. attorney, with Mr. Smith working under that office.

The prosecutors pointed to the Justice Department’s set of regulations governing the appointment of special counsel as statutory authority, and argued that the source of funding was a nonissue because Congress has enacted permanent indefinite appropriations to “pay all necessary expenses of investigations and prosecutions by independent counsel appointed.”

What Does This Mean?

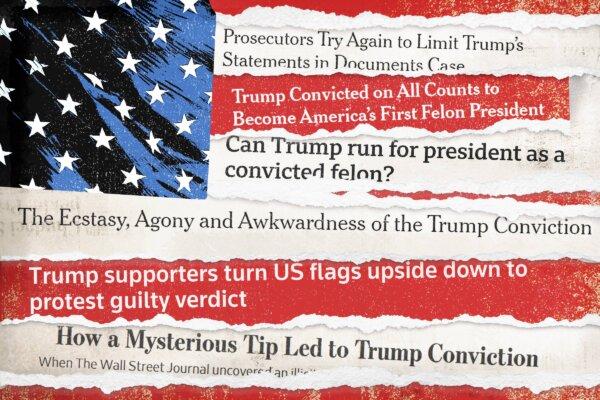

In an op-ed, Mr. Calabresi wrote that allowing Mr. Smith to continue his prosecution could result in a conviction that gets overturned solely because a higher court deems Mr. Smith’s appointment unconstitutional years after the fact. The possibility is heightened by the fact that six Supreme Court justices hold similar views to him on the Appointments Clause, Mr. Calabresi argued.“Every action that he has taken since his appointment is now null and void,” he wrote.

Mr. Calabresi elaborated on the implications of an attorney general allowed to grant any individual such enforcement power.

“We do not want future U.S. Attorney Generals, such as the ones Donald Trump might appoint, if he is re-elected in 2024, to be able to pick any tough thug lawyer off the street and empower him in the way Attorney General Merrick Garland has empowered private citizen Jack Smith,” he wrote. “Think of what that would have led to during the McCarthy era or in the Grant, Harding, Truman, or Nixon Administrations in all of which an Attorney General was corrupt.”

“A ‘special counsel’ should be appointed in the manner constitutionally mandated for the appointment of other high-level executive branch officials: nomination by the President and confirmation by the Senate,” Justice Kavanaugh wrote.

Former federal prosecutor John O’Connor told The Epoch Times that the issue of Mr. Smith’s authority was “pretty much black and white.”

Mr. O’Connor agrees partially with the amici in that a person in Mr. Smith’s position needs Senate confirmation and that the correct avenue would have been to appoint a U.S. attorney.

Mr. Smith was also previously part of the Justice Department, as chief of the public integrity section, which Mr. O’Connor argues undermines the independence that his appointment was supposed to bring.

“He hasn’t been independent at all,” Mr. O’Connor said. Diverging from the amici, Mr. O’Connor said he believes that the Justice Department regulations do permit the attorney general to appoint special counsels but that they must be truly independent, so as not to treat such appointments as a “fig leaf” purporting independence.

Mr. O’Connor argued that Mr. Smith’s long tenure at the Justice Department showed that he knew his “marching orders.”

“I think Garland picked Smith because he’s a dogged guy and he can count on Smith not to back off and not to exercise any discretion in favor of Trump,” Mr. O’Connor said.

In Mr. O’Connor’s reading of the Mar-a-Lago case, the majority of the charges on retaining classified information warrant dismissal, “but the charges of lying and obstruction are not ridiculous.”

Of course, he says, “nobody wants to hear it.” Supporters of President Trump won’t look at the merits of any of the charges because of the “unfairness” of the case overall, while those who dislike President Trump don’t want to hear that any of the charges are bad, Mr. O’Connor said.

Had a truly independent prosecutor taken on the case, there might have been a sense of discretion and moderation, he said, instilling public confidence in the justice system. The prosecutor might have considered only the few legitimate charges, and “he may not have brought them,” Mr. O’Connor said.

“He might have thought that, in the exercise of discretion, one shouldn’t do it,” he said.