When opera singers from the 20th century come to mind, people think of Luciano Pavarotti, Maria Callas, and Beverly Sills. However, some opera singers’ legacies have faded into the past and are forgotten by even the most ardent opera fans.

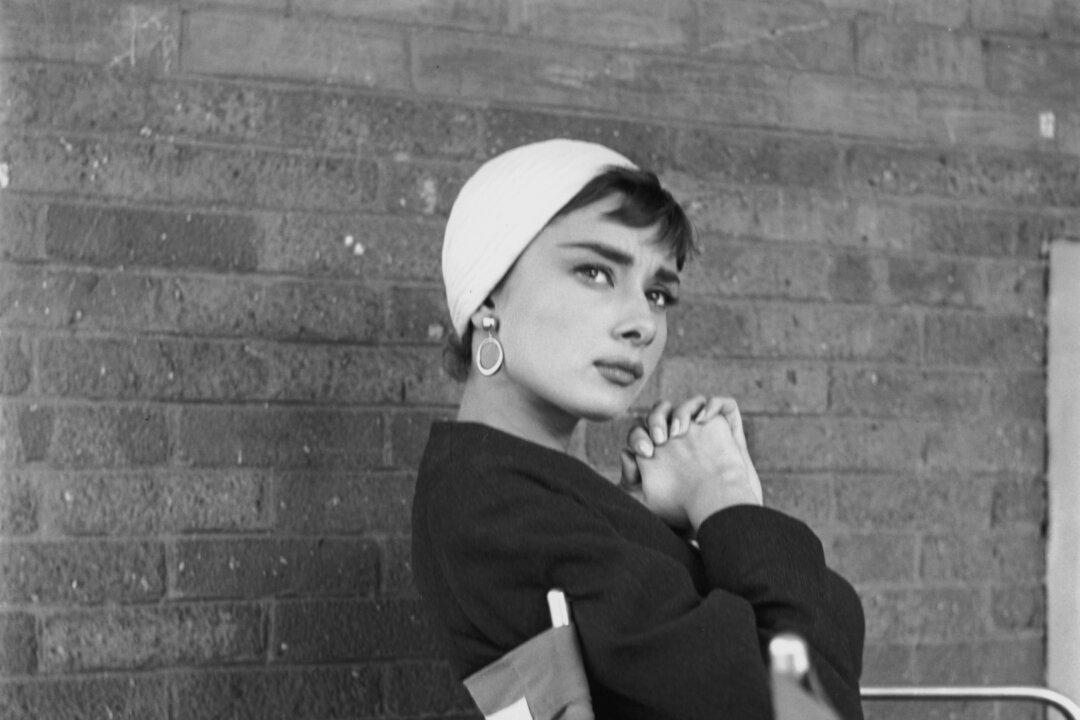

One such singer is Marion Talley (1906–83). This soprano played an important role in the legacy of American opera, yet her name is more likely to be recognized by Hollywood historians than by opera lovers. Besides being a Metropolitan Opera star for a brief time, she provided the first voice heard by moviegoers in a synchronized sound film.

This singer’s interesting story came from a reader with a personal connection to Talley. Although Richard Rudiak insists he is no expert on her life, he has researched her story to expand on his firsthand experiences with her, which took place years after her brief operatic stardom. As a student and fan of Hollywood history and opera, I was fascinated by her life and career.

In 1922, she played the title role in Ambroise Thomas’s “Mignon” at the Kansas City Grand Opera at age 15. She received enthusiastic support from local residents, including $10,000 to support her further studies. Using that money, she studied with vocal coach and accompanist Frank LaForge in New York. In 1923, she auditioned for the Metropolitan Opera but wasn’t hired.

The next year, she returned to Kansas City and gave four concerts to raise money for further studies in Italy. In 1925, she returned to the United States. In 1925, she was hired for the Metropolitan Opera’s 1925/26 season by general manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza.

Movies and the Met

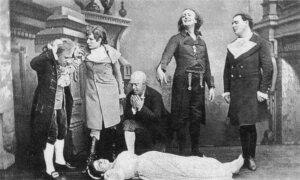

On Feb. 17, 1926, Talley made her debut as Gilda, the leading lady in “Rigoletto” by Giuseppi Verdi. At age 19, she became the youngest singer to have starred at the Met (her record was broken by 18-year-old Patrice Munsel in 1943). Gatti-Casazza wanted to keep the publicity surrounding her debut to a minimum, but the proud folks of Kansas City had other plans.The mayor and 200 fans from her hometown rented a special train for the trip. As 10,000 people crowded into the theater to see the celebrated prodigy, tickets were resold for many times their worth, and standing room was $25 per person (about $445 in today’s currency). It was called the $100,000 premiere. Although she became a household name, critics were less enthusiastic about her singing, calling her “immature.”

Despite the critical response to her Met debut, Tally continued to sing starring roles at the famous opera company for the next four years. Meanwhile, Hollywood came knocking on her door, since the film industry was always eager to capitalize on a public sensation. On Aug. 6, 1926, the American public got to see and hear Talley’s performance as Gilda for themselves on the big screen.

Warner Bros. debuted the new Vitaphone sound-on-disc process for a synchronized soundtrack in its film “Don Juan.” The technology would be used to make the first mainstream talking picture, “The Jazz Singer,” the next year. Before the film, the Vitaphone technology was demonstrated in eight shorts. These opened with a speech from Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America president Will H. Hays, before continuing to seven classical music shorts.

The fifth short is Talley singing “Caro nome” (“Dear name”), the famous aria from “Rigoletto.” She is accompanied by the Vitaphone Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Herman Heller. This isn’t just a concert performance of an aria; she’s in full costume and on a beautiful set from the opera, complete with an elaborate staircase.

Although various technologies for synchronizing sound with film had been tested since the earliest days of motion pictures in the late 1800s, DeForest Phonofilm presented the first public screening in 1923. Developer Lee de Forest started with 18 shorts of popular vaudevillians, opera singers, and ballet dancers, which he debuted at the Rivoli Theater in New York City.

Her Legacy

Mr. Rudiak was personally involved in Talley’s story during her later years and grew interested in her career and legacy. Speaking about biographies of the former opera singer’s life, he wrote:“They all fail to mention that she moved to Nevada and worked for [my father] George Rudiak during the 1950s until about 1965. That Marion had to enter the job market to work for dad strikes me as both interesting and truly extraordinary since, as I recall reading ... during her heyday, Marion earned about $5,000 per week. ... My thoughts are that Marion’s retreat to the desert oasis of Las Vegas makes sense at a very basic human level. To me, this appears to have been Marion’s way of escaping both her notoriety and what I am beginning to conclude was her deep sense of personal shame from both having fallen from grace within the operatic community—and never having [been] able to re-establish that career in any meaningful capacity, for whatever those reasons might have been—and for having had a child out of wedlock in an era when that had a far more negative resonance in society than it does today. When I knew Marion, few people, if any, seemed to connect her to ‘The Met’, film, or ... anything else in the arts for that matter.”

Elaborating further on their relationship, Mr. Rudiak recalled: “When I was a child, Marion Talley was my ‘grown-up’ friend. ... It was not until just recently—60 years after having known her—that I learned anything about the full extent of her professional career on the opera stage and of her importance in film, and only because I started doing some research to record some family memoirs. ... My relationship with her was very simple. Marion typically took my calls whenever I phoned my father’s office. ... I did, on numerous occasions, meet with her whenever I was at my father’s office. I distinctly recall that she was very kind, hummed a good deal, enjoyed the song ‘God Didn’t Make Little Green Apples’ by Bobby Russell, and told me, on numerous occasions, that she was going to perform at Carnegie Hall but, before she could, ’her voice gave out.’ Those last words were hers, not mine. In all honesty, her comment about Carnegie Hall meant very little to me when I was a child.”

Now that he knows Talley’s full story, Mr. Rudiak is very interested in helping his childhood friend achieve her goal of singing at Carnegie Hall, albeit posthumously. Feb. 17, 2026, will be the 100th anniversary of her debut at the Metropolitan Opera. To commemorate this landmark anniversary in classical music, Mr. Rudiak is campaigning to have Talley’s first Vitaphone short played at Carnegie Hall on that date. He has also contacted the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) to suggest that they honor Talley at the 2026 Academy Awards ceremony for the significant role she played in the advent of sound films.

I applaud Mr. Rudiak’s efforts to honor this prodigiously talented singer from the past. As a young operatic soprano myself, I deeply relate to her story. Talley’s brief yet brilliant career is an inspiration to all young singers and a beautiful example that talent and technique aren’t connected to age.