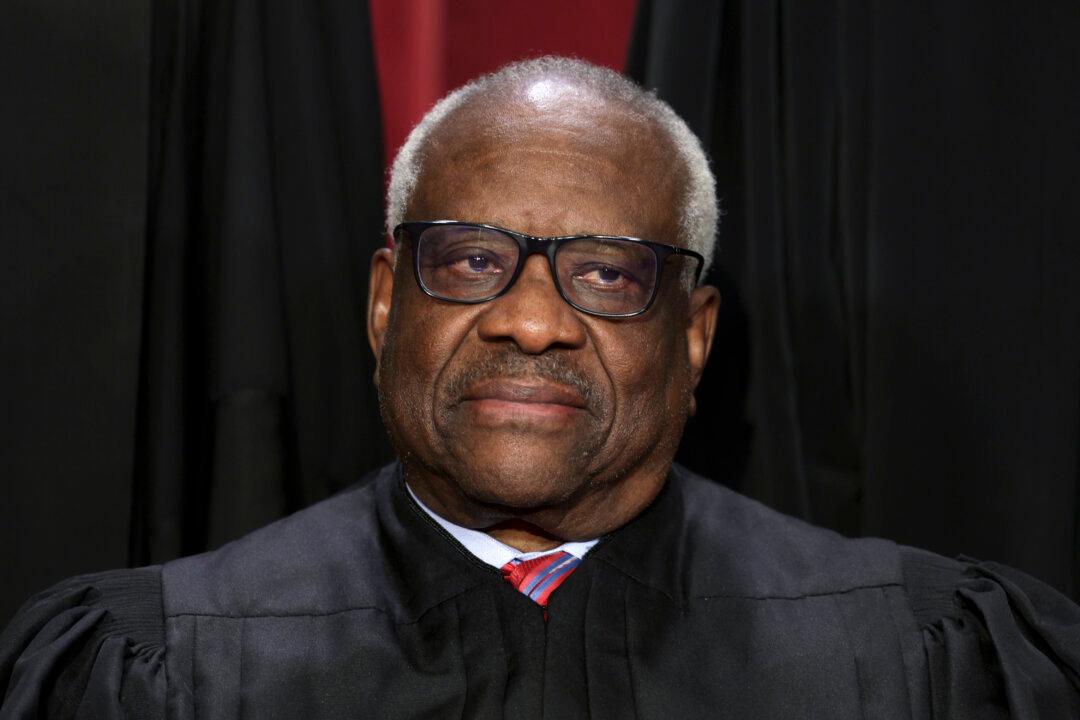

Justice Clarence Thomas criticized the landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling this week, days after its 70th anniversary, suggesting in a redistricting case that the Supreme Court used faulty reasoning when it declared that it was unconstitutional to separate schoolchildren by race.

This is a problem because the same defective thinking appears in the court’s redistricting decisions, according to the court’s longest-serving justice.

Brown was actually two decisions.

In the first ruling on May 17, 1954, the court unanimously overturned the “separate but equal” principle established in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) in a challenge to public school segregation in Topeka, Kansas. The court held that government-sanctioned separation by race violated the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, a decision that bolstered the civil rights movement.

On May 31, 1955, in a decision known as Brown II, the court unanimously ordered the states to go ahead with desegregation plans “with all deliberate speed.” Some constitutional scholars criticized the decision for upending precedent and writing new law based on data presented by social scientists.

There was considerable resistance in some states until 1957, when Republican President Dwight Eisenhower, who had personally been lukewarm to Brown, decided that he was constitutionally obligated to enforce the rulings. He federalized the Arkansas National Guard and used it to protect minority high school students in Little Rock, Arkansas, where Democrat Gov. Orval Faubus had been resisting desegregation.

Justice Thomas’s statement came in a concurring opinion filed on May 23, which upheld a congressional redistricting plan in South Carolina. The court found in Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP that the map was adopted because of political considerations and wasn’t a product of race-based discrimination.

The Supreme Court treats racial gerrymandering as constitutionally suspect but allows partisan gerrymandering.

The ruling benefits Republicans who face upcoming elections in November as they defend their razor-thin majority in the U.S. House of Representatives. The seat in South Carolina’s First Congressional District is currently held by Rep. Nancy Mace (R-S.C.).

The court majority held that challengers failed to demonstrate that race was the main factor in the redistricting, as opposed to more mundane partisan considerations.

Redistricting, which the Constitution primarily entrusts to state legislatures, is “an inescapably political enterprise,” Justice Alito wrote.

Justice Clarence Thomas joined the majority opinion except for one part and filed his own separate opinion concurring in part. Justice Elena Kagan filed a dissenting opinion that was joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson.

Courts Shouldn’t Handle Gerrymandering Claims: Justice Thomas

In his concurring opinion, Justice Thomas suggested that courts should not be involved in adjudicating gerrymandering claims at all.“Racial gerrymandering and vote dilution claims lack judicially manageable standards for their resolution. And, they conflict with the Constitution’s textual commitment of congressional districting issues to the state legislatures and Congress. They therefore present nonjusticiable political questions,” he wrote.

If a question is nonjusticiable, it means that it can’t be assessed according to legal principles by a court.

“The Court should extricate itself from this business and return political districting to the political branches, where it belongs,” the justice added.

Citing various court decisions in his opinion, Justice Thomas wrote that the court in Alexander overstepped its authority by embracing a “view of equity ... [that] emerged only in the 1950s,” he wrote. In law, “equity” refers to the power that courts possess to provide fairness outside the technical requirements of the law.

The Supreme Court’s “impatience with the pace of segregation” caused by resistance to Brown led the court “to approve ... extraordinary remedial measures.”

In Brown II, the court “took a boundless view of equitable remedies, describing equity as being ‘characterized by a practical flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a facility for adjusting and reconciling public and private needs.’”

That approach justified temporary measures to overcome resistance at the time, but “as a general matter, ‘such extravagant uses of judicial power are at odds with the history and tradition of the equity power and the Framers’ design.’”

Federal courts have the power to provide only the equitable relief “traditionally accorded by courts of equity,” but “not the flexible power to invent whatever new remedies may seem useful at the time.”

The remedies in redistricting cases “rest on the same questionable understanding of equitable power,” Justice Thomas wrote.

“No court has explained where the power to draw a replacement map comes from, but all now assume it may be exercised as a matter of course,” he added.

“The lack of a historically grounded map-drawing remedy is an enormous problem for districting claims, because no historically supportable remedy can correct an improperly drawn district.”

Meanwhile, on May 23, in Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, the Supreme Court ordered part of the case remanded to a three-judge federal district court “for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.”