After receiving thiamine supplementation for a few days, her symptoms improved, and her heart function quickly recovered.

Vitamin B1, also known as thiamine or thiamin, earned its name due to being the first B vitamin to be discovered.

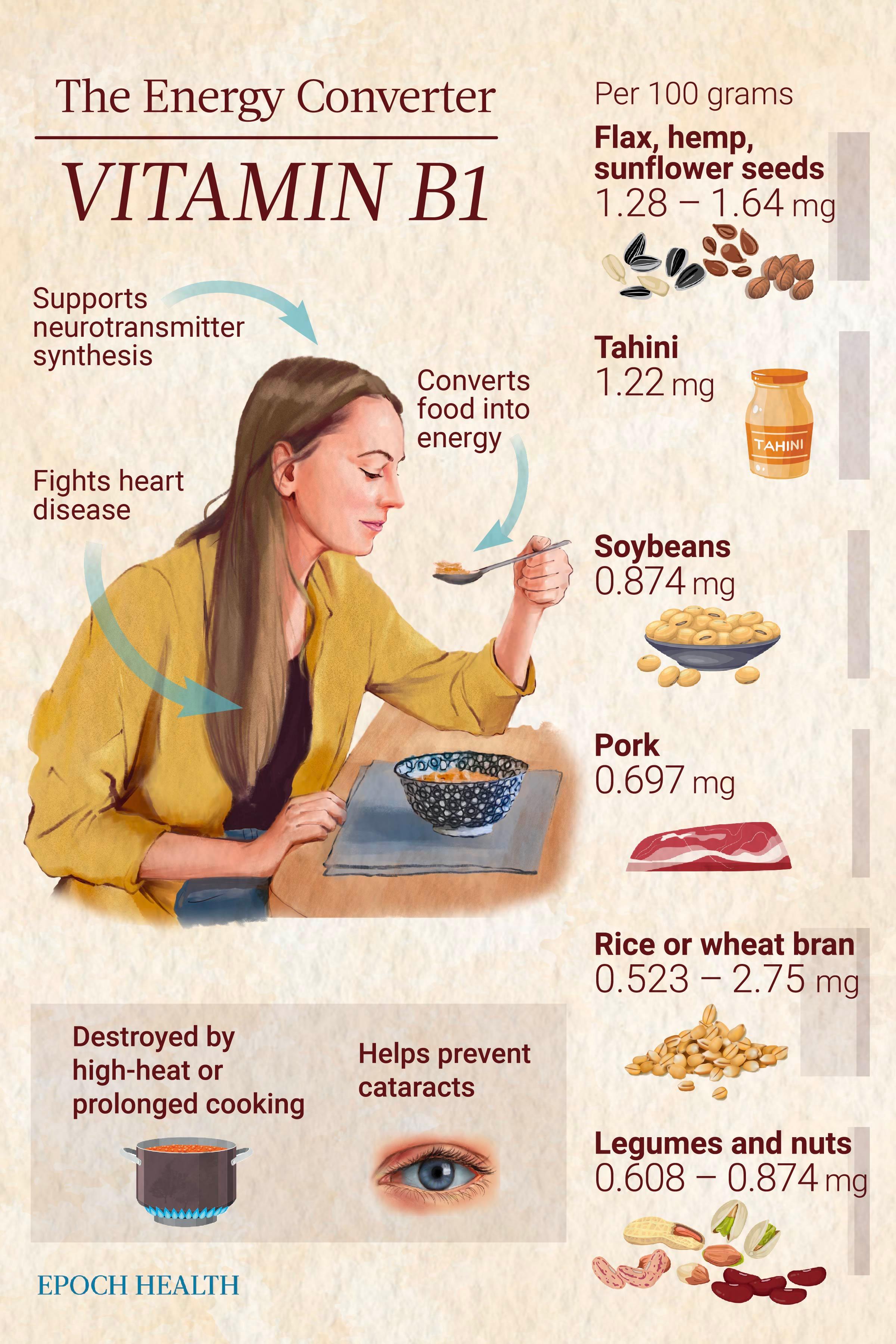

This water-soluble vitamin assists with several fundamental cell functions and helps the body convert food into energy. Its main benefits include improving neurological function, boosting heart health, and preventing infection.

Flax, sunflower, and hemp seeds, pistachios, black beans, and pork are among the best dietary sources of vitamin B1. However, if none of these appeals to you, this article provides additional food options.

Unfortunately, vitamin B1 deficiency often goes undetected, as seen in the case of the 47-year-old woman. Between 20 percent and 90 percent of various patient groups may have a deficiency.

What Are the Key Health Benefits of Thiamine?

1. Improves Nervous System and Brain Function

Thiamine, as well as other B-complex vitamins, are essential for proper nervous system and brain function.Thiamine is also critical for supporting the synthesis of neurotransmitters, influencing cognition, mood, and memory.

2. Prevents Heart Disease, Such as Heart Failure

One primary function of vitamin B1 is maintaining proper levels of acetylcholine. Acetylcholine deficiency can affect cardiac function since the nervous system uses this neurotransmitter to communicate with the heart. Consequently, symptoms such as chest pain, high blood pressure, or congestive heart failure may arise.3. Reduces Depression

Excessively high levels of acetylcholine can contribute to depression or anxiety, whereas vitamin B1 can help balance levels.4. Fights Infectious Diseases

B vitamins are also known as “anti-stress” vitamins due to their potential immune system support and stress resilience enhancement. They also possess antiviral properties and help shield immune cells from oxidative stress damage.5. Converts Food Into Energy

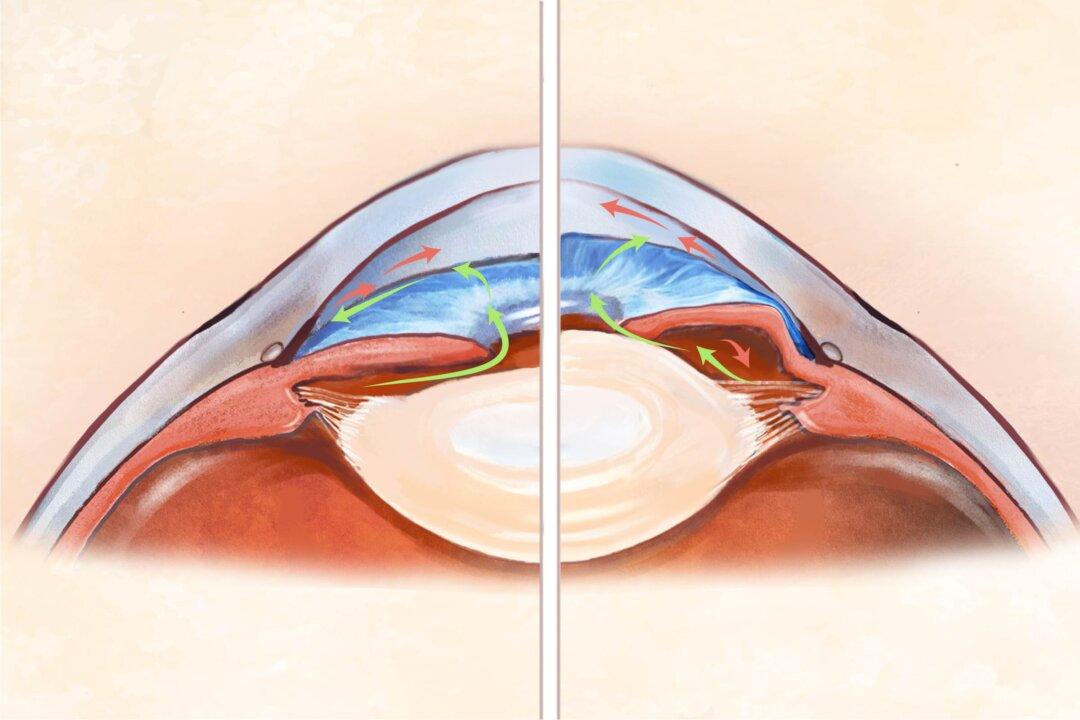

Thiamine plays a crucial role in converting carbohydrates into energy by serving as a cofactor for enzymes that break down glucose, the main energy source for cells. In addition, our bodies also require thiamine to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a universal energy source in the body.6. Protects Against Cataracts

Thiamine and other essential nutrients such as protein, vitamin A, and other B-group vitamins may reduce the likelihood of cataract formation.7. Combats Diabetes and Obesity

A lack of thiamine seems to disrupt the pancreas’ usual insulin production and worsen high blood sugar levels. In a 2013 study, 12 hyperglycemic individuals were given 300-milligram thiamine supplements daily for six weeks. Unlike the placebo group, the group taking thiamine experienced an improvement in fasting blood sugar, insulin, or insulin resistance. The researchers concluded that high-dose thiamine supplements might help prevent the worsening of fasting blood sugar and insulin levels and enhance glucose tolerance.8. Lowers Cholesterol

Thiamine protects against the thickening of arterial smooth muscle cells involved in worsening the narrowing of the arteries in arteriosclerosis. It correlates negatively with triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels (“bad” cholesterol) and positively with high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels (“good” cholesterol). One study involving Type 2 diabetes patients found thiamine increased HDL after supplementing for three months, but the authors noted that more well-designed, randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm the vitamin’s potential to raise HDL. In healthy older individuals, higher plasma thiamine levels are connected to lower total cholesterol concentrations, potentially delaying vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis.9. Staves Off Inflammatory Diseases

Thiamine has been found to influence the immune system by lessening inflammation and oxidative stress, which can harm immune cells and contribute to the onset of different illnesses, such as infections, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and asthma.What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Thiamine Deficiency?

Thiamine deficiency can often mimic common metabolic conditions and is not necessarily caused by a lack of intake but rather by ongoing exposure to substances that counteract thiamine’s effects or inhibit the body’s absorption.

There are two types of thiamine deficiency: primary and secondary.

- Fatigue

- Muscle pain and weakness

- Anxiety

- High blood pressure

- Painful peripheral neuropathies: Pain in the hands, feet, and calves with increased sensitivity, reduced feeling, and problems with movement.

- Brain fog

- Weight loss and loss of appetite

- Depression

- Reduced immunity

- Irritability

- Chest and abdominal discomfort

- Increased heart rate

Beriberi (Wet and Dry)

Thiamine deficiency leads to markedly impaired carbohydrate digestion. This interferes with energy generation, increases harmful free radicals, and decreases neurotransmitters, leading to beriberi.Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome

This syndrome is more common in the United States than beriberi. It combines both Wernicke’s encephalopathy and Korsakoff’s psychosis.The former manifests as problems with movement, nystagmus (involuntary, rapid, and repetitive side-to-side eye movements), ataxia (a lack of coordination and control of voluntary movements), ophthalmoplegia (weakness or paralysis of the muscles that control the eyes), and altered consciousness. If not treated, Wernicke’s encephalopathy can eventually lead to coma or even death.

What Are the Different Types of Thiamine?

Natural Sources

- Thiamine (vitamin B1): This is one of the naturally occurring forms of thiamine found in different foods.

- Thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP): Also known as thiamine diphosphate (TDP), TPP is the biologically active form of thiamine. It plays a crucial role in energy metabolism, including the breakdown of glucose, lipids, and proteins. It is also found in food.

- Allithiamine: This is a naturally occurring disulfide derivative of thiamine found in various Allium plant species. It is formed enzymatically when the garlic bulb is cut or crushed. Allithiamine possesses potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Its synthetic form is called thiamine tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide (TTFD).

Synthetic Sources

- Thiamine mononitrate (TMN): A synthetic thiamine salt, which is a stable form of thiamine, it is commonly used in supplements and fortified foods. It is converted into TPP in the body.

- Thiamine hydrochloride (THCl): This is another synthetic thiamine salt used in supplements and food fortification. Like TMN, it is converted into TPP in the body but has a notably slower degradation rate.

- Benfotiamine: A synthetic precursor of thiamine with enhanced lipid solubility and higher tissue penetration and bioavailability, it allows for better absorption in the body to prevent thiamine deficiency. Research suggests that benfotiamine has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.

What Are the Dietary Sources of Thiamine?

Although science often focuses on studying the benefits of individual nutrients, it’s important to remember that nutrients interact in complex ways in real life. For instance, when you add a spoon of flax seeds to your breakfast cereal, you’re not just getting a dose of vitamin B1 but also consuming a whole food with many different nutrients and compounds, some of which we may not fully understand yet.

- Yeast extract spread (23.4 milligrams)

- Crude rice bran (2.75 milligrams)

- Flax seeds (1.64 milligrams)

- Dried sunflower seeds (1.48 milligrams)

- Hulled hemp seeds (1.28 milligrams)

- Tahini (1.22 milligrams)

- Black beans (0.9 milligram)

- Soybeans (0.874 milligram)

- Pistachios (0.87 milligram)

- Whole dried sesame seeds (0.791 milligram)

- Quaker organic instant oatmeal (0.73 milligram)

- Pork (0.697 milligram)

- Pecans (0.66 milligram)

- Rice bran bread (0.653 milligram)

- Peanuts (0.64 milligram)

- Brazil nuts (0.617 milligram)

- Red kidney beans (0.608 milligram)

- Buckwheat (0.539 milligram)

- Ham (0.468 milligram)

How Can I Optimize the Intake and Absorption of Thiamine?

- Avoid high-heat cooking: Thiamine is sensitive to high heat and prolonged cooking and leaches into water, resulting in its loss during cooking or soaking.

- Eat less ultra-processed food, carbs, and sugar: Eating too many carbs and sugar can reduce the thiamine in the body and inhibit its absorption. Since thiamine can also be removed during food processing, to compensate for these losses, thiamine is often enriched or added back to processed foods.

- Avoid drinking too much coffee, tea, and alcohol: Compounds found in coffee and tea, such as tannins and anti-thiamine factors, can hinder thiamine absorption in the gastrointestinal tract or reduce the amount of thiamine in the body. Increased thiamine loss in urine can occur due to factors such as alcohol misuse. Alcohol can interfere with the absorption and metabolism of thiamine and increase the body’s demand for it.

- Keep a calm mind: Exposure to any type of stress leads to higher energy usage and an increase in the body’s metabolic rate. As thiamine is essential for energy production, the increased metabolic activity during stress can increase the body’s demand for thiamine and reduce thiamine levels more rapidly.

- Be mindful of certain medications and treatments: Diuretics increase urine production and can lead to greater excretion of thiamine and other water-soluble vitamins in the urine. Long-term treatment with seizure medications can lower the levels of B vitamins, including vitamin B1, by interfering with thiamine absorption. In addition, stomach bypass surgery changes the digestive tract’s structure and reduces the stomach’s size, which can reduce the absorption of nutrients such as thiamine. In later sections, you'll find other drugs that could interact with vitamin B1.

- Conditions that increase thiamine requirements: hyperthyroidism (excess thyroid hormone), pregnancy, breastfeeding, intense physical activity, and fever.

- Conditions that obstruct thiamine absorption: prolonged diarrhea, gluten-induced gastrointestinal damage, celiac disease, and Crohn’s disease.

- Disorders that hinder thiamine metabolism: liver and kidney diseases and metabolic disorders. Certain genetic defects have been identified that impair thiamine transport and metabolism, namely defects in SLC19A2, SLC19A3, SLC25A19, and the TPK1 gene.

- Conditions that increase thiamine loss: diabetes. Decreased thiamine levels could result from increased thiamine clearance by the kidneys in these patients.

Which Nutrients Boost Thiamine’s Effects?

What Types of Thiamine Supplements Are Available?

- Multivitamins: Multivitamins containing vitamin B1 can come in the form of children’s chewable tablets and liquid drops. They usually provide at least 1.2 milligrams of thiamine.

- B-complex vitamins: This product contains all eight vitamin Bs, usually providing 1.5 milligrams of thiamine or more. Since consuming a single B vitamin over time can lead to an imbalance in vitamin B group intake, many experts advise using B-complex vitamins.

- (Natural) thiamine: Some over-the-counter thiamine supplements and multivitamins contain natural thiamine extracted from guava, holy basil, and lemon.

- Thiamine hydrochloride (THCl): Synthetic thiamine salts—TMN and THCI—are the most commonly used forms of thiamine supplements. They are both stable and water-soluble. However, they are considered less healthy than the supplements made with naturally occurring thiamine, as they are derived from coal tar, hydrochloric acid, or acetonitrile with ammonia. Nutritionist Judith DeCava believes THCl is harmful since it can initially alleviate fatigue, but over time, it may lead to increased fatigue due to the accumulation of pyruvic acid.

- Thiamine mononitrate (TMN): Although TMN is commonly used, some consider it unhealthy because it’s synthetically produced from the same sources as TCIHCI.

- Benfotiamine: Benfotiamine is a synthetic form of thiamine that has been chemically modified. This modification makes benfotiamine more fat-soluble compared to regular thiamine. As a result, benfotiamine can penetrate cell membranes more easily and is more readily absorbed by the body, leading to higher thiamine levels in tissues and cells. Although it’s synthetic, benfotiamine is generally considered safe and has many health benefits.

- Thiamine tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide (TTFD): TTFD supplements have been used extensively to maintain health and treat diseases, and they’re generally considered safe for long-term supplementation.

What Are Other Ways to Get Thiamine?

What Is the Recommended Dietary Allowance of Thiamine?

Optimal blood thiamine level was not used to develop these recommendations, as blood thiamine levels are not dependable indicators of thiamine status.

Health professionals and scientists have differing opinions on thiamine’s recommended dietary allowance (RDA), mainly focusing on the ideal dosage to prevent deficiency and promote optimal health.

The current RDAs are shown in the table below:

Depending on the severity of the condition, people with thiamine deficiency may need a significantly higher amount for treatment—up to 500 milligrams.

How Can I Test My Thiamine Levels?

- Blood tests: Although blood tests lack accuracy in diagnosing thiamine deficiency, as they do not reflect the actual thiamine levels within cells, doctors still often conduct them to check electrolyte levels to rule out other potential causes of symptoms.

- Erythrocyte transketolase test: The level of erythrocyte transketolase activity indicates disruptions in thiamine metabolism. The erythrocyte transketolase test can evaluate thiamine levels by measuring transketolase activity before and after adding TPP. More than a 25 percent increase in activity may reflect an abnormal result. However, this test’s specific normal range values have not yet been defined.

- High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC): HPLC is a technique used in analytical chemistry to separate, identify, and quantify components of a mixture, such as a blood sample. A more advanced analytical method is liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. It is also the most commonly used technique to measure thiamine phosphorylated esters in the patient’s serum or blood sample.

- Echocardiogram: An echocardiogram uses ultrasound to produce images of the heart. It assesses heart function and helps identify reasons behind cardiac symptoms. For instance, it can detect whether or not thiamine deficiency is behind heart failure.

- Radiographic studies: Radiographic studies refer to diagnostic imaging techniques that use radiation to create detailed images of the internal body. As Wernicke’s encephalopathy involves symmetric changes in the thalamus and many other parts of the brain, imaging tests can detect these abnormalities.

What Are the Side Effects of Thiamine?

High-dose intravenous thiamine can also cause a sudden, temporary narrowing of the airways in the lungs called bronchospasm, leading to difficulty breathing, coughing, and other symptoms.

Which Medications Interact With Thiamine?

- Diuretics lead to a greater excretion of thiamine in the urine.

- Digoxin, a medication for heart conditions, might hinder heart cells’ absorption and utilization of thiamine, especially when combined with furosemide, a loop diuretic.

- Phenytoin: Certain individuals (not all) on phenytoin, a drug for epilepsy and seizures, may experience reduced thiamine levels in their blood after prolonged use, potentially affecting the drug’s side effects.

- 5-Fluorouracil is a chemotherapy drug used to treat different cancers. It blocks the process of turning thiamine into its active form, TPP, resulting in lower thiamine levels.

- Erythromycin belongs to a class of antibiotics called macrolides, used for various bacterial infections. It has been linked to reduced thiamine levels in patients, likely because it hinders thiamine transport.

- Patiromer is commonly used to manage high potassium levels in the blood. It can bind to some orally administered drugs, including thiamine, in the gastrointestinal tract, thus preventing their absorption.

- Oral contraceptives affect the body’s thiamine metabolism, potentially leading to deficiency.

- Metformin, commonly used to manage Type 2 diabetes, can contribute to thiamine deficiency, as it can inhibit a type of thiamine transporter in the body.