What Are the Types of Tick-Borne Diseases?

- Lyme disease: 62,551

- Anaplasmosis: 5,633

- Babesiosis: 1,915 (2021 statistics)

- Ehrlichiosis: 1,582

- Spotted fever rickettsiosis (SFR): 1,271

What Are the Symptoms and Early Signs of Tick-Borne Diseases?

- Fever

- Chills

- Headache

- Muscle aches and pains

- Nausea or vomiting

Lyme Disease

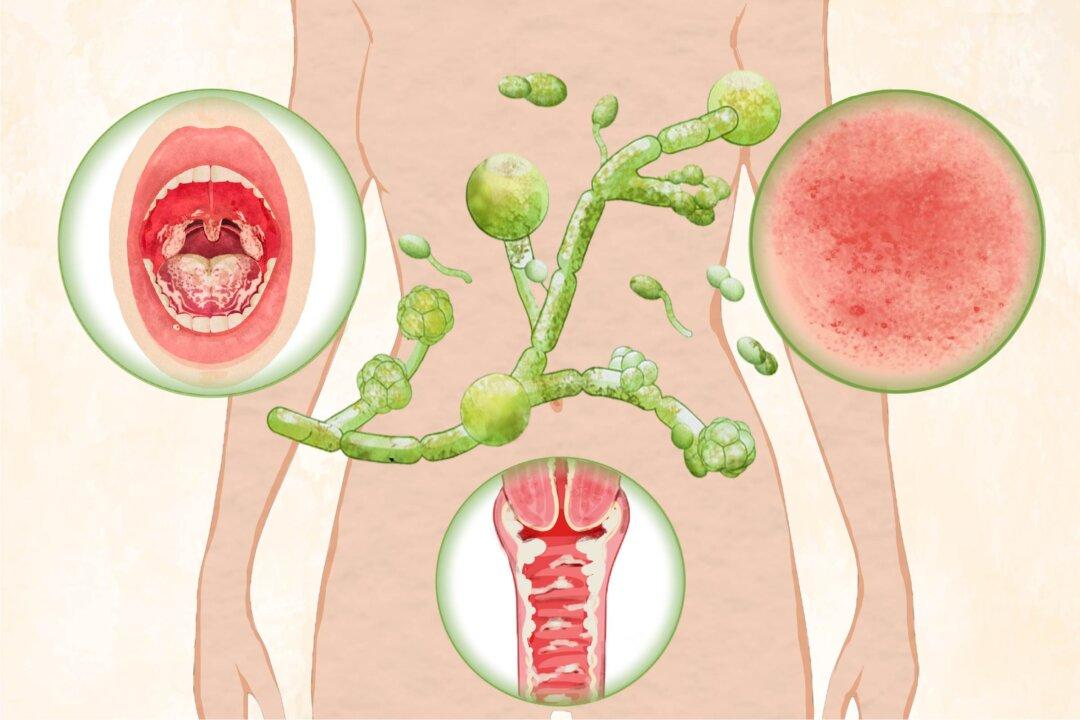

Apart from those listed above, the most characteristic symptom of Lyme disease is the bull' s-eye rash that sometimes appears, along with fatigue.Anaplasmosis

Anaplasmosis symptoms usually appear one to two weeks after an infected-tick bite, which is often painless and may go unnoticed. The symptoms are typically mild to moderate in the early stages (days one to five). Fever is usually the initial symptom. Additional symptoms specific to the condition include diarrhea and loss of appetite.Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis (SFR)

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is the most dangerous type of spotted fever, and symptoms include fatigue, loss of appetite, and a rash after an incubation period of three to 12 days. The skin rash usually starts as spots on the wrists and ankles, spreading to the trunk and sometimes the palms and soles, and it typically appears two to five days after the fever begins. About 10 percent of RMSF patients never develop a rash.Ehrlichiosis

After an incubation period of five to 14 days, patients infected with ehrlichiosis may experience general discomfort, diarrhea, changes in mental state (e.g., confusion), rash, and the symptoms listed above.Babesiosis

Babesiosis infection can vary from showing no symptoms to being life-threatening, with approximately 25 percent of infected adults and 50 percent of children asymptomatic. Compared to other tick-borne diseases, babesiosis has a relatively long incubation period, ranging from one to four weeks after a tick bite to 24 weeks after a contaminated blood transfusion.What Causes Tick-Borne Diseases?

Lyme Disease

Among tick-borne diseases, Lyme disease is the most prevalent in North America. According to the CDC, newer calculations using alternative approaches indicate that around 476,000 individuals could receive a diagnosis of Lyme disease annually in the United States instead of the nearly 63,000 cases reported to the authorities. Lyme disease is transmitted by blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis or Ixodes pacificus) carrying the bacterium, sometimes called a parasitic spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi through their bites.While “Bitten” raises thought-provoking questions, the scientific community supports the natural origin of Lyme disease, suggesting there is evidence of its long existence in North America.

Anaplasmosis

Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis (SFR)

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is the most serious SFR infection and the most lethal tick-borne disease in the United States. Other types found in America include Tidewater spotted fever (aka Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis), Pacific Coast tick fever, and Rickettsialpox.Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis, previously called human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME), is an illness caused by at least three bacterial species in the United States: Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia ewingii, and Ehrlichia muris. The lone star tick carries E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii, mainly in the south-central and eastern states. In contrast, the blacklegged tick, found only in Wisconsin and Minnesota despite the blacklegged tick’s broader distribution in the eastern United States, carries E. muris eauclairensis. Ehrlichiosis can also be transmitted through blood transfusion or organ transplant, although only in rare instances. It most commonly infects monocytes (white blood cells).Babesiosis

Babesiosis is caused by microscopic parasites and transmitted mainly through the bite of blacklegged ticks and the western blacklegged tick, infecting red blood cells. Most babesiosis cases occur in the Northeast and upper Midwest, especially in regions such as New England, New York, New Jersey, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.Who Is at Risk of Tick-Borne Diseases?

- Outdoor workers like park rangers, landscapers, construction workers, farmers, forestry workers, and individuals working on railroads and oil fields

- Outdoor enthusiasts, including hikers and campers

- People living in endemic areas: Those residing or spending time in regions where tick-borne diseases are prevalent, such as wooded areas in the northeastern and upper Midwestern United States, Rocky Mountains, and Atlantic and Pacific Coasts, are at an increased risk.

- Owners of pets and livestock: Animals such as cattle, cats, and dogs can carry ticks, increasing the risk of tick bites for their owners.

- Immunocompromised individuals: People with weakened immune systems, such as those undergoing chemotherapy or organ transplant recipients, may be at higher risk of developing severe symptoms if infected with tick-borne diseases.

How Are Tick-Borne Diseases Diagnosed?

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification: PCR amplification is performed on DNA from blood samples, with the method being most sensitive during the first week of illness and becoming less sensitive after starting antibiotics. A positive PCR result is helpful, but a negative result doesn’t rule out the diagnosis, so treatment shouldn’t be delayed based solely on a negative result. PCR-based tests are useful in distinguishing Babesia from Plasmodium falciparum in cases where blood smear results are unclear, confirming infection in patients with low parasite levels, and identifying the specific Babesia species involved. Importantly, PCR tests can take weeks to receive results.

- Indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) test: The usual blood test for diagnosing anaplasmosis is the IFA test for a type of immune protein called IgG. Doctors often perform two IgG IFA tests: one when you become sick and another a few weeks later when your condition improves. However, antibody levels might be too low to detect in the first week of illness, so a single test can’t confirm anaplasmosis. IFA testing using Babesia microti antigens is helpful in detecting antibodies in patients with low parasite levels, but it can yield false negatives in those infected with different Babesia species.

- Blood-smear microscopy: During the initial week of illness, a blood smear under a microscope might show microcolonies of anaplasmae in certain white blood cells, strongly suggesting anaplasmosis. However, this method isn’t very reliable on its own for diagnosing anaplasmosis. Babesiosis is typically diagnosed by detecting Babesia organisms in blood smears.

- Skin biopsy: If the patient has a rash, a skin biopsy from the rash site is recommended. If there is an eschar, a sample can be collected using a swab or punch biopsy. Tests such as PCR or immunohistochemical staining can yield quick results. However, a negative result shouldn’t delay treatment if clinical signs point to RMSF.

- DNA test: Doctors can test for Rickettsia DNA in the patient’s blood samples, or the scab of the eschar can be collected for DNA testing.

What Are the Complications of Tick-Borne Diseases?

- Anaplasmosis: In rare cases, delayed treatment or concurrent medical conditions can lead to severe illness, manifesting as respiratory failure, bleeding issues, organ failure, and death.

- Spotted fever rickettsiosis (SFR): If RMSF is not treated in time, a patient may eventually suffer from coma, nerve injury, brain swelling, breathing difficulties, necrosis (tissue death), loss of hearing, bladder control issues, partial paralysis, gangrene, organ damage, and death. For the other types of SFR, although complications and death are uncommon, they are more likely in older or debilitated patients.

- Ehrlichiosis: Severe complications may include uncontrolled bleeding, seizures, coma, organ failure, septic shock, and death.

- Babesiosis: Serious complications are acute respiratory failure, organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation (severe abnormal blood clotting), coma, and death.

AGS is life-threatening and causes an allergic reaction to red meat. Symptoms include flushing, hives, itchy skin, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and anaphylaxis. In the United States, AGS is most often linked to the lone star tick, but other ticks—especially the blacklegged tick—have not been ruled out as carriers.

What Are the Treatments for Tick-Borne Diseases?

After tick removal, clean the bite area and your hands with soap and water or disinfect the area with alcohol. Keep the tick in a sealed container and note the date, location of the bite, and the body part affected. Monitor yourself for symptoms in the coming weeks.

Antibiotics

- Doxycycline: The primary treatment for Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, SFR, and ehrlichiosis is doxycycline, continued for five to seven days after the patient improves and is fever-free for 24 to 48 hours. In the case of RMSF, doxycycline treatment will last for at least three days after fever reduction and clinical improvement, with a minimum course of five to seven days. Although other antibiotics can be used for treatment, this raises the risk of severe illness and mortality. Suspected early Lyme disease is treated for 10 to 14 days. Children under 8 years old often receive an alternate antibiotic due to the risk of permanent teeth staining with doxycycline.

- Atovaquone plus azithromycin: Combining these two antibiotics is the preferred regimen for babesiosis.

- Quinine plus clindamycin: This combination is an alternative regimen to the preferred one for babesiosis, but it is also widely accepted as the standard treatment for severely ill patients.

Exchange Transfusion

In severe cases of babesiosis where the parasite level in red blood cells is very high (over 10 percent), doctors may use exchange transfusion, during which blood is slowly drained from the patient and replaced with fresh and prewarmed donor blood.How Does Mindset Affect Tick-Borne Diseases?

- Prevention: A proactive mindset toward outdoor activities, such as wearing protective clothing and using insect repellent, can reduce the risk of tick bites.

- Early detection: Being aware of the symptoms of tick-borne diseases and seeking medical attention promptly can lead to early diagnosis and treatment, thus improving outcomes.

- Treatment adherence: A positive mindset can help individuals stay motivated and optimistic, which may make them more likely to follow their doctor’s instructions and adhere to their treatment plan.

What Are the Natural Approaches to Tick-Borne Diseases?

1. Medicinal Herbs

The late American herbalist Stephen Harrod Buhner, the author of many books about natural healing, presented a basic protocol for anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis in his book “Natural Treatments for Lyme Coinfections: Anaplasma, Babesia, and Ehrlichia.” The Epoch Times could not verify the efficacy of the protocol, but the medicinal herbs and compounds are as follows:- Redroot sage (Salvia miltiorrhiza): Redroot sage (Danshen in Chinese) has been used medically in Asia for over two millennia.

- Houttuynia species: The chameleon plant (Houttuynia cordata) is the better-known Houttuynia species. It’s widely used as a culinary and medicinal herb. Many studies have confirmed its pharmacological effectiveness against inflammation, cancer, viruses, bacteria, hyperglycemia, and obesity.

- Genistein: Genistein is a phytoestrogen found in soybeans and soy products. It belongs to the isoflavones class. Genistein acts similarly to natural estrogen in the body and is used as a supplementary medicine for women’s health issues.

- Chinese skullcap (Scutellaria baicalensis): Chinese skullcap has a history in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for addressing allergies, infections, inflammation, cancer, and headaches. Additionally, it shows potential for antifungal and antiviral properties in lab studies.

- Cordyceps: Cordyceps is a type of fungus that grows on insect larvae. Over 350 species of Cordyceps have been identified globally, each associated with specific fungi and insect hosts.

- Kudzu (Pueraria lobata): Kudzu’s root extract may prevent weight gain and enhance how the body processes glucose.

- Astragalus: Astragalus is often used with other herbs as a dietary supplement for various conditions such as respiratory infections, allergic rhinitis, asthma, chronic fatigue syndrome, and chronic kidney disease. It also possesses immunomodulatory, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties.

- Dong quai (Angelica sinensis): Dong quai is a medicinal herb used in TCM. Research on dong quai’s human use is limited, but preliminary lab tests indicate that it may have pain-reducing properties, promote blood vessel dilation, and affect uterine muscle activity.

- Licorice (Glycyrrhiza genus): Licorice has antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory properties.

- Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera): Also known as Indian ginseng, ashwagandha is a crucial herb in Ayurvedic medicine. It boosts brain and nervous system function, supports reproductive health, and strengthens the body’s ability to handle stress.

- Milk thistle (Silybum marianum): Milk thistle may be used as a dietary supplement for hepatitis, cirrhosis, jaundice, diabetes, indigestion, and other conditions.

- Chinese/Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng)

- Cryptolepis sanguinolenta

- Sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua)

- Chinese skullcap (Scutellaria baicalensis)

- African Christmas bush (Alchornea cordifolia)

- Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum)

The study also found that certain natural compounds from Cryptolepis sanguinolenta, sweet wormwood, and Chinese skullcap worked just as well as or better against Babesia duncani than the combination of quinine and clindamycin, standard antibiotics used to treat babesiosis.

2. Nitric Oxide-Releasing Therapy

Nitric oxide (NO) is a gas our bodies use to fight harmful invaders like bacteria, viruses, and parasites. It helps immune cells communicate and produces chemical reactions that kill these pathogens. When immune cells release NO, the gas enters the invaders’ cells and damages them, helping our bodies defend against infections.3. Essential Oils

Several researchers from the above study also discovered that 10 essential oils were effective against Babesia duncani in a 2020 study. These included garlic, black pepper, tarragon, palo santo, coconut, pine, “meditation,” cajeput, moringa, and “stress relief.” In a hamster red blood cell culture model, placed directly on the bacteria at a low concentration of 0.001 percent, these oils all showed inhibitory activity against Babesia duncani.How Can I Prevent Tick-Borne Diseases?

Avoid Tick Exposure

- In tick-prone areas, avoid soil and wooded and brushy areas with tall grass and leaf piles.

- Stick to the middle of trails when walking.

- Avoid sitting directly on the ground or stone walls.

- Trim shrubs and trees in the backyard for sunlight to pass through.

- Establish a one-yard-wide barrier using wood chips, mulch, or gravel between your lawn and wooded areas, shrubs, or stone edges.

- Seal openings in stone walls to deter deer and rodents from entering your yard.

- Position patios, decks, and playground sets in sunny spots away from yard borders, and place playground sets on a surface of mulch or wood chips.

- Wear light-colored, tightly woven clothing to detect ticks easily.

- Wear enclosed shoes, long pants, and a long-sleeved shirt. Tuck your pants legs into socks or boots and your shirt into pants.

- Keep long hair tied back, especially during gardening.

- Consider using netting on strollers and playpens to minimize the need for repellents around them.

- Regularly check clothes and exposed skin for ticks when outdoors.

Repel Ticks

You can use the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) website to find a product that suits your needs. Use minimal repellent on children, and avoid applying it to their hands to prevent accidental exposure to the eyes or mouth. Here are a few options:- DEET products: Apply repellents with 20 percent to 30 percent DEET (N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide) on both skin and clothing for several hours of protection. DEET should be used carefully in young children due to reported toxic reactions, but some sources claim that certain DEET products are considered safe for children over 2 months old. Regardless, avoid using DEET products with a concentration of over 30 percent.

- Permethrin: Permethrin is unique among repellents as it not only repels but also kills ticks and insects on contact. Treating clothes and gear with 0.5 percent permethrin can make them protective through multiple washes.

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE): OLE is a natural repellent derived from eucalyptus trees. Its synthetic form is called P-menthane 3,8-diol. Some other types of essential oils may also be used to repel ticks. However, the effectiveness of volatile essential oils tends to decrease pretty quickly, so diligent application is necessary.

- Picaridin: Also known as KBR 3023, picaridin is a clear and almost odorless ingredient used in repellent products.

- Pet repellents: Safe repellents are available for your pets; consult your veterinarian about them.

- Conduct a thorough tick check at the end of the day for yourself, children (especially their hair), and pets, and remove ticks promptly. Be aware that most ticks crawl up the body from the ground or one’s leg brushing against grass or very low brush. Check under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, in and around the hair, between the legs, and around the waist.

- Shower or bathe soon after coming indoors, preferably within two hours.

- Tumble dry clothes on high heat in a dryer for 10 minutes to kill ticks, as ticks may survive washing cycles.